Alma Söderberg on Travail

Choreographer Alma Söderberg presented her piece Travail in avant-premiere at the Working Title Platform the night before the salon. Guided by six collages she had brought to the salon, Söderberg talked about Travail as both a practice and a performance.

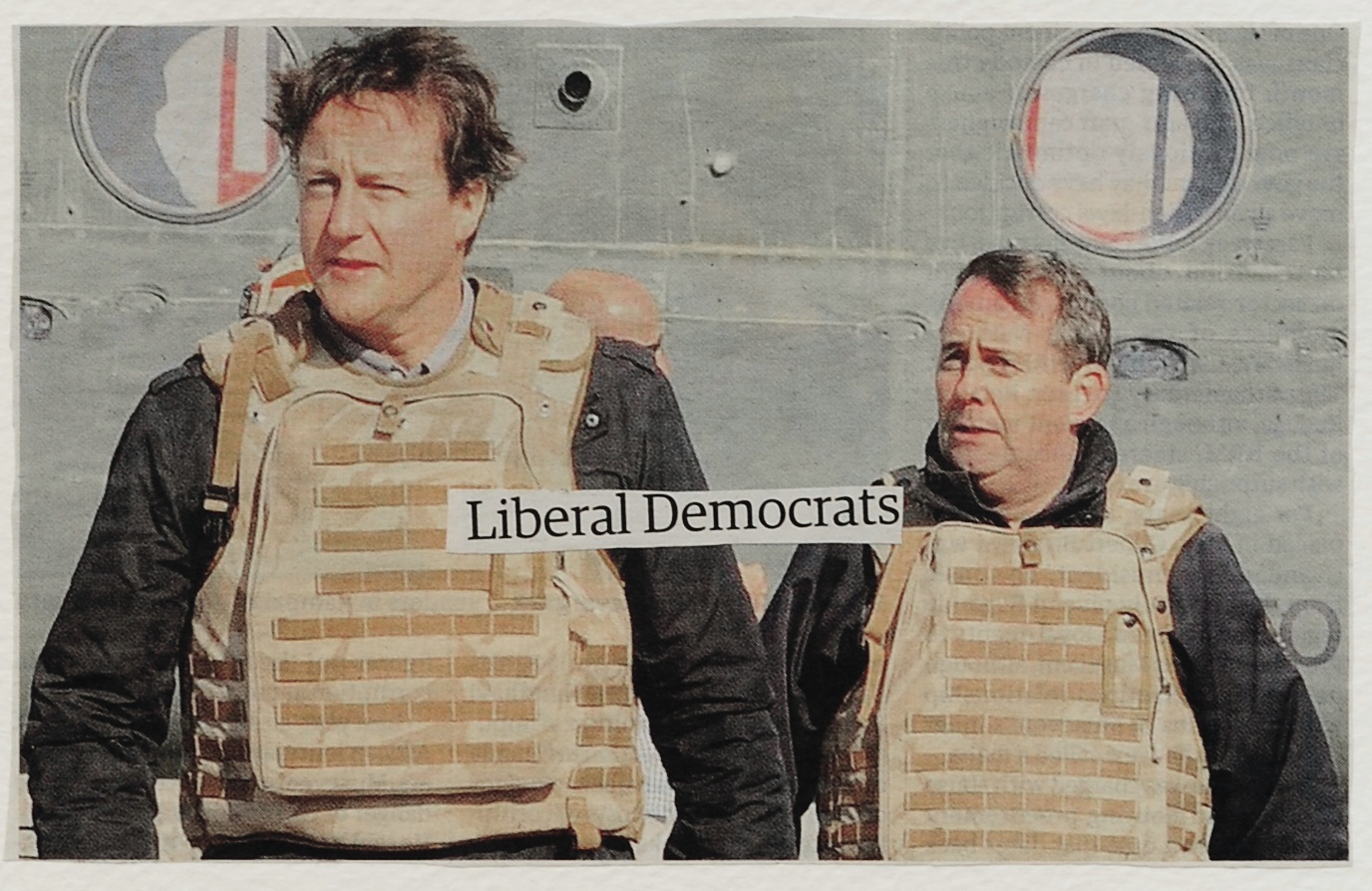

“Words, images, phrases, spaces, colours and texture are some of the many things to be found in the daily newspaper. I practice reading the newspaper with scissors in my hand cutting out things that for known or unknown reasons catch my attention. Playing with combining the fragments, I build new information and open up space for ‘other’ meanings to occur. I later create scores out of these collages. I practice them over and over until premiering, not choosing in which way the fragments of thought and imagery should be expressed but rather trying not to censor any form.”

As her work comes into being through daily repetition, Söderberg’s collages and scores also define a particular approach to dramaturgy. How did she collaborate with dramaturge Igor Dobricic for Travail? “The challenge is to avoid actively producing meaning in advance, but rather to get to that through the collages by treating them as a map and a compass. Curiously, both Igor and I are very talkative, so suspending our dramaturgical habits wasn’t obvious. We tried to create long silences, almost as an inhibition exercise. We called that ‘trying not to understand the piece’.”

Later on, the notion ‘practice’ was taken up in the discussion, as an activity that has particular rules and is sustained over a long period of time, so new meanings and ideas can emerge from that. Söderberg said in this respect: “I’m interested in emergence and serendipity, but I stay with the materials, working the present. In the arts a lot of people talk about possibilities and promises, they project things into the future. Still, you have to do it, so that’s why I rather speak about work than about practice.”

Introduction

Dilettantism currently finds a revival in the performing arts. Practices outside of one’s formal training migrate into the work in order to thwart habits and expectations. Bricolage and collage spur on a basic desire of making, in confrontation with materials that are often simply at hand. How do dilettant practices and practising dilettantism operate as artistic strategies? What does it mean to work with materials? With a collection or archive of materials? How do these materials provide resistance to our questions and perhaps establish an arbitrary contract? How can the practice of an amateur inform professional practices? Is there an interest in ‘unlearning’ things?

Due to unforeseen circumstances, the presentation of choreographer Jennifer Lacey’s Guided Consultations in the Archives of Amateur Dramaturges To Resolve Problems of Life and Creation had to be cancelled last minute, as well as Lacey’s participation in the salon. The salon in the end consisted of a conversation with choreographers Alma Söderberg and Rodrigo Sobarzo. Since the sound recording of the salon partially failed, this page documents elements of the salon as a collection of materials (sound, image, text) on dilettantism awaiting further discussion and resonance.

Credits

June 16th, 2012, 4.30pm at Working Title Platform, Kaaistudio’s Brussels

Concept and moderation: Jeroen Peeters

Guests: Jennifer Lacey, Rodrigo Sobarzo and Alma Söderberg

Production: Sarma @ WorkSpaceBrussels

IMAGES ALMA SÖDERBERG

Rodrigo Sobarzo on collecting images and music

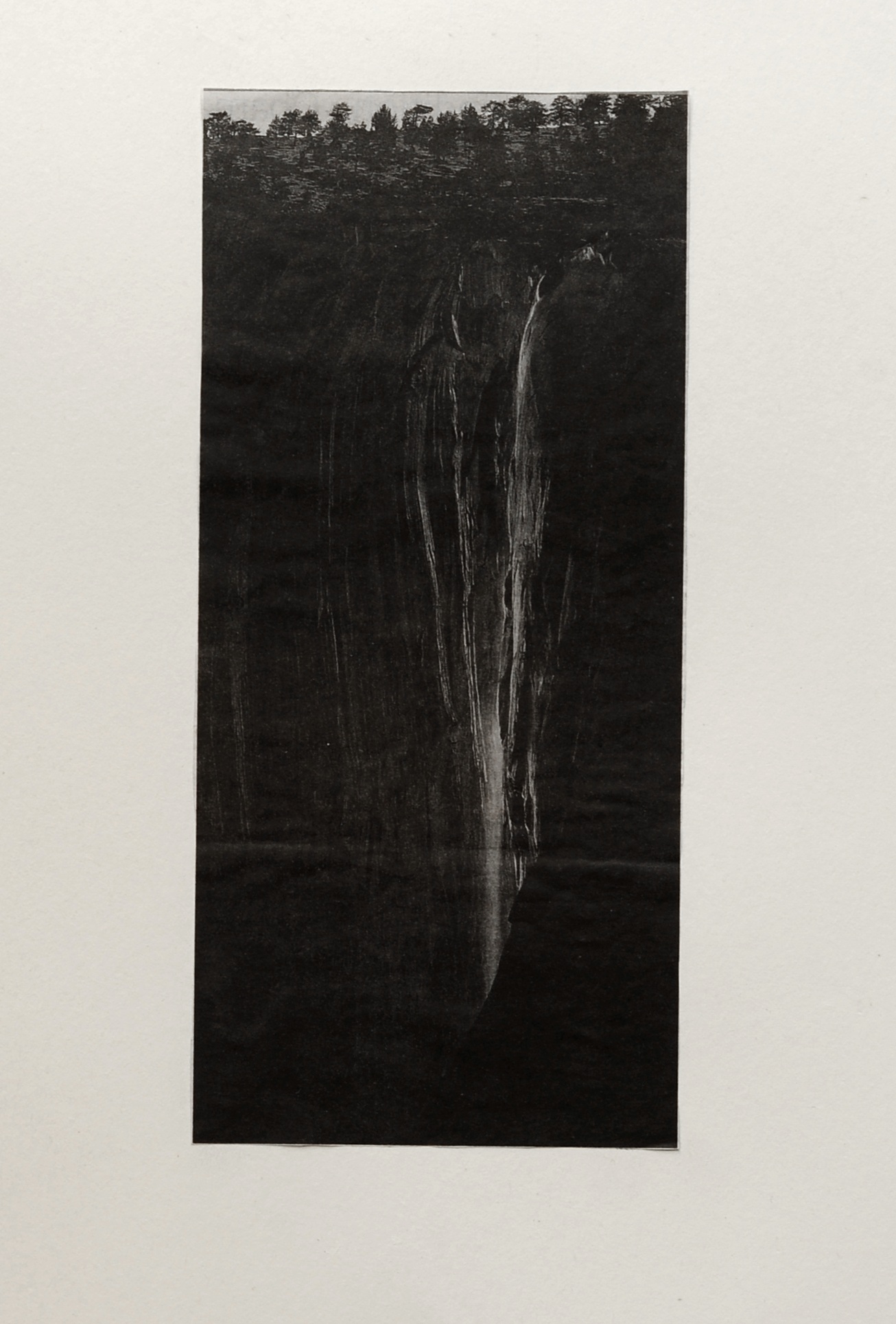

Choreographer Rodrigo Sobarzo studied together with Alma Söderberg at the SNDO in Amsterdam and collaborates with her as a set designer or “space man”. On his daily visits to blogs, he collects images and music that catch his attention. As a reference, he brought two materials to the salon. First a randomly chosen image that fascinates him and also featured on the salon’s invitation flyer.

And second a self-interview by Brian Eno from his 1982 album From Brussels with Love, in which he discusses his practice and approach to music. Sobarzo appreciates an attitude that goes beyond both naming interests and emotional attachment.

One way of creating mobility and novelty as an artist is for Brian Eno connected to dilettantism: “For me the great strength of dilettantism is that it tends to come in from another angle. It doesn’t always of course, the other way of being a dilettante is just by doing the most pedantic and obvious things. But an intelligent dilettante will not be constrained by the limitations of what’s normally considered possible. He won’t be frightened, he’s got nothing to lose. You know, a person who has his career at stake on every piece of work is obviously going to be a bit more defensive about what he does; whereas the dilettante, who just kind of says ‘O, I try this for a while…’, he is not so frightened of failure, I would imagine. But to maintain a dilettante attitude consciously is also rather suspicious. I guess I passed the dilettante phase now, I have decided that I am a musician, or a composer, and that’s what I do. I can’t generally pretend to be naive anymore, though I’m still musically naive, in a sense.”

Later in the discussion, Sobarzo returned to the idea of practice as “a daily routine” that relieves him from constantly identifying his interests or actively constructing meaning. “I know my daily routines and when I do them, something else can unconsciously emerge.” What takes over are the materials at hand, which in the case of Sobarzo’s scenographic activity also include spaces, that is the actual space of the studio or the theatre in which the performances take place. “Rather than bringing in a foreign element to charge a certain place or context, I work with what is already there. My spatial practice is indeed this: revealing the space that is already there.”

Both the materials and the daily routine establish an arbitrary contract that allows for practices and interests to migrate — an understanding of dilettantism Sobarzo picked up in several workshops with Jennifer Lacey. “In her workshop Fake Art Therapy we had to propose treatments for each other, just on the basis of things that were around. So I had to look in my backpack for books or songs and create therapeutic routines, even though they were totally invented. Jennifer makes you fully belief in the fiction. Through that I understood that whatever you are doing or whatever your interest is, you should pay attention to it and fully embrace it, whether it’s your profession or not. For me that’s certainly an important aspect of dilettantism.”