Interview

About this interview

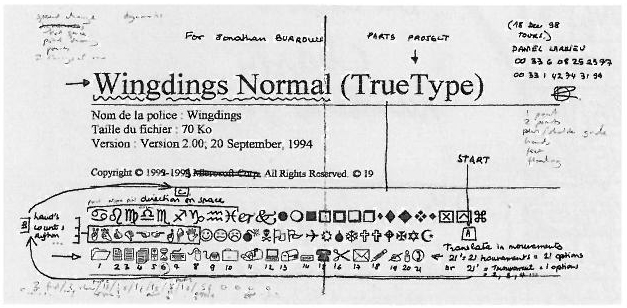

This interview with English choreographer Jonathan Burrows was conducted by Myriam Van Imschoot on April 14 2055, in preparation of the publication ‘What’s the score’ on the use of notational systems and scores in recent contemporary dance productions that she compiled as a guest editor (in collaboration with visual artist Ludovic Burel) for the French journal Multitudes. The interview took place in a public space, a bar, somewhere in Brussels. Jonathan brought to the meeting a set of scores, working materials, that are leafed through.

Text annotations to the interview

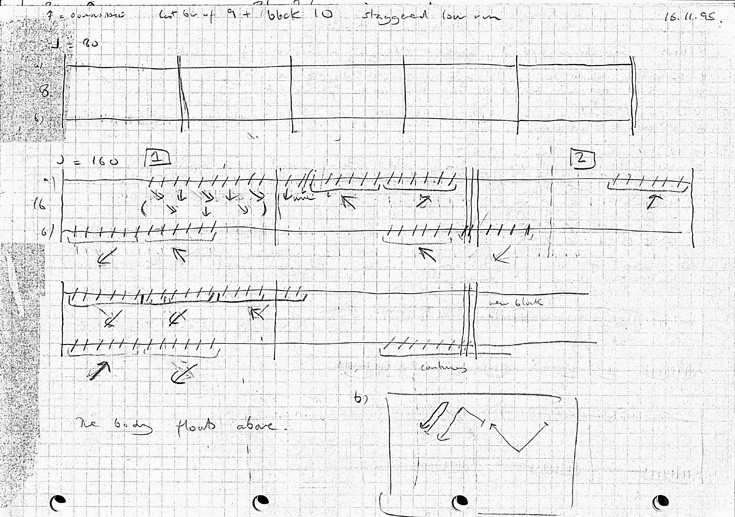

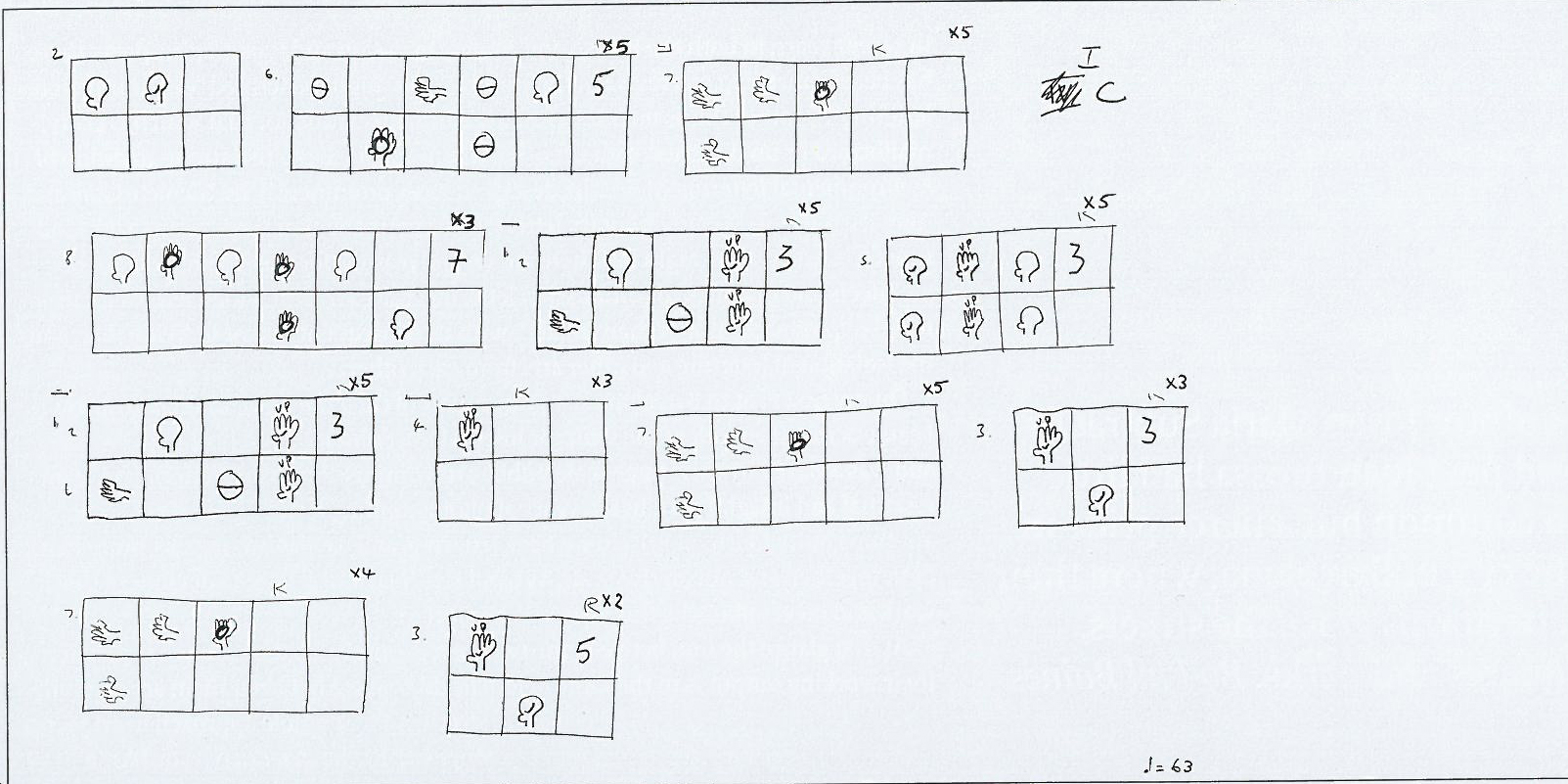

In a nearly one hour long interview Burrows explains the way in which he works with scores, giving mostly examples from his choreographies: the film choreography Hands (1995), The Stop Quartet (1996), Both Sitting Duet (2002). Hands, made for television in 1995, for the BBC/Arts Council, was the first time Jonathan worked with a score. However, The Stop Quartet, a piece for four dancers made in 1996, is the first score discussed here.

00:00:15 00:00:23

Jonathan Burrows introduces the principles of The Stop Quartet.

00:00:23 00:01:53

Matteo Fargion assisted Burrows in making the score for The Stop Quartet. One of the other musical collaborators for that piece, Kevin Volans, had introduced them to a scored way of working by Shobana Jeyasingh, a South Indian choreographer, based in London, who previously worked with Volans. Burrows is interested in Jeyasinghs method to use graph pahper, but when trying to compose in a similar way he “ran into a mess” and with the help of Matteo he then used another related notational system based on an African method of notating rhythm systems.

“So I tried to work on graph paper when I was starting to work on The Stop Quartet and I really ran into a mess and I got really confused. Although I could sense the germ of something that was going to be interesting but it got way too complicated. Having worked for a month or something I went back to Matteo and showed him this stuff on graph paper, which he simplified (…) This score here is what Matteo suggested that I try to work with and according to him it has some connection with how African rhythmic systems are written down. You have a line who represents one person playing, and you have a mark on the line which respresents when the sound is played.”

00:03:1700:03:47

In the course of the creation Burrows develops his notation into a more graphic visualization of the rhythm. He finds it a problem that the only clear way to foreground rhythm is by using footsteps (The Stop Quartet) or punctuated gestures (Both Sitting Duet), but this apparent visualization of rhythm can become less clear when the whole body is implied.

00:03:4700:04:13

At first, the score is used as a preparation before joining rehearsals with the dancers.

00:04:1300:05:06

Burrows and Myriam Van Imschoot try to decipher the score that they are holding in their hands.

00:05:06 00:06:42

The score of The Stop Quartet applies to the whole body, but in this piece the feet are primary. Burrows explains how visual rhythm works for him: in order to read the rhythm you need a strongly defined downbeat, best provided by the feet.

“In a way Both Sitting Duet and the problem with the Stop Quartet was that I could never make a satisfactory piece afterwards that went on from here, because it could only be ever be this, footsteps. I mean that was how the Stop Quartet worked, and it worked like that but if I make another piece it would be the same piece. So Both Sitting duet is kind of the same thing, but the visual rhythm can be evident because it has to do with clearly punctuated gestures, which was an other way to do it. But whenever I tried to do it using the whole body the rhyhtm disappears, you know. Then you need to find the rhythm somewhere else, in the sound that is accompanying it or something that you might speak or sing or something.“

00:06:42 00:10:47

The Stop Quartet is discussed even more in detail. It’s sections, length, number of dancers, etc.

00:10:4700:11:31

Burrows explains why scores are useful. In general, Burrows atttributes several useful reasons to work with scores. It’s a way to prepare in a clear and complex way for rehearsal. Although Burrows hasn’t been working as such with dancers for ten years now, he describes his memory of that moment of working in the studio with other people as potentially filled with anxiety, because there are always moments when you don’t know what to do, and the presence of the others can be blocking. “This was just a way for me to prepare.”

00:11:31 00:14:02

The second reason is to proceed more quickly in the sequential composition. One can overcome the need to memorize something first physically before one moves on.

“Both sitting duet – in terms of working with the score - was similar. I would say often to Matteo “we better go back and over this because we don’t know, we will forget it” and he would say “no, let’s keep going on, because if we keep going on then we are moving now, and if we go back we will get stuck thinking too hard what we are doing”. It’s not that what we were doing was arbitrary. It isn’t about arbitrariness. The principles that we were working with in Both Sitting Duet and the Stop Quartet were clearly researched, thought out and researched physically as well. By the time we set off with this way of working that allowed for a certain innocence, we were confident enough about the principles that we had found to take our hands of them. It’s not that we went forward blindly.”

00:14:02 00:16:50

A third (related) reason is to avoid holding onto an image, when performing a piece. You tap directly into the conditions of production (more than focusing on the desired result). Scores makes one not reproduce the image one has of performing something, but going back to the score one can always retap into the conditions of the movement production.

“Suddenly we started performing the image. And that’s only the image of it, not the thing itself. We had to work quite hard to find ways away from the image. It’s the audience who is privileged to see the image, not the performer. When the performer tries to hard to get hold of the image, the thing that is happening is often gone. So for me working with scores in dance is about avoiding the trap of the image of the thing becoming dominant rather than the thing itself. The score allows this ability to put the thing into a different kind of information that can then be put aside and retrieved, and if I don’t have that, the act of memorizing the thing seals the image and then the image itself can trap me. I think this is also a personal thing, about me and how I work. There must be people who work brillliantly with the image itself. Different things work for different people.”

00:16:50 00:18:06

Burrows considers doing The Stop Quartet again, and reflects on the function of the score so many years later.

00:18:32 00:21:21

Myriam goes back to an earlier point in the interview and asks whether the dancers would ever get the scores or work with them? Burrows says he can’t remember but after relistening to this interview in 2011 he adds: The dancers in The Stop Quartet did initially work directly with the scores, it was a shared resource rather than a private tool for him as a choreographer. However, as the piece developed and the scores became more complex, then sometimes they didn’t pause to catch everyone up as to how the scores were working, but rather communicated in whichever way was most useful for that moment. In other words the score remained a practical thing, rather than a rigid methodology.

00:18:57 00:21:21

A score is a usefull tool for communicating the rhythm visually and it can then be performed physically more easily. Burrows illustrates this by singing a score.

00:21:21 00:22:54

Myriam goes back to an earlier point in the interview where they discussed the scores of Shobana Jeyasingh. She asks why Burrows didn’t include her scores in the article he wrote for a graphic publishing magazine. Myriam explains the visual characteristics of the scores that will be selected for the publication of Multitudes.

00:22:54 00:25:16

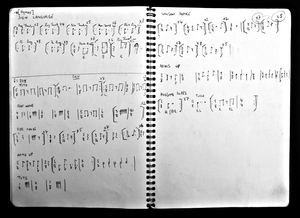

More explanation about certain symbols in the scores of Burrows.

00:25:18 00:28:06

The concept of The Stop Quartet was to layer sound, light, movement. There are holes in the layers which allow one element to pierce through the other. The principle was also used for the film version. Myriam refers to the peeping hole quality of the film. Burrows says this was not the prior motivation: it was more about looking for ways to find equal weight between different mediums within the performance, so that the watcher would be able to read through and between the counterpoints of movement, music, light and film.

00:28:0600:30:50

Burrows does not always work with scores, but when he does “it’s more to clarify the principles of a piece” and “to communicate with his collaborators”. Since The Stop Quartet he has found many other ways to work.

At the time when the interview was conducted he was working with Matteo Fargion on The Quiet Dance (2005), at a moment in the process when the two were trying to keep their hands empty to see what might also be possible. Unlike The Stop Quartet or Both Sitting Duet, The Quiet Dance was not written first and realised afterwards, but rather physicalised first and then recorded as a score later.

00:30:5000:34:19

Burrows draws here another useful distinction: there’s scores to describe what already exists and those who help you to arrive at what you don’t know yet what it’s going to be. “By finding principles of how to work and how to organize those thoughts on paper you might arrive at something you don’t know what it’s going to be and how it will manifest itself. It allows you to work with deeper principles of the thing.”

Discussing the interview more recently Burrows adds (2011): “For me, one pleasure of a score is to come back to the body with information which the body must figure out, in the process of which you momentarily break habitual patterns. The only thing I am wary about in relation to scores, is when they become too much an object, something fetished as though they are special beyond the piece itself.”

00:34:1900:37:33

Myriam refers to a quote of Lisa Nelson and how she values scores when they set up the terms for possible sets of relationships (rather than a score just being a sequence of tasks). It’s about what is emerging more than how one obeys prescribed sequent tasks. Burrows explains he works sequentially, but although sequence is still very dominant, he looks for what Lisa Nelson points out.

00:37:3300:38:19

Burrows speaks about freedom in a score (cf. quote)

00:38:1900:38:53

More information on signs and symbols used in a score by Burrows. Coming back to a score after all this time, Burrows sometimes has forgotten what a particular notation means.

00:38:5300:40:26

Myriam goes back to an earlier point of the interview where Burrows spoke about the function of a score as a way to prepare for rehearsals. “You need some way to think about what you are going to do, before you go into rehearsal”. Burrows quotes Kevin Volan. He continues to say how the process of working with Jan Ritsema allowed him a different relation to preparation, moving beyond scores to a more conceptualised approach based on finding strong principles for working.

00:40:2600:44:59

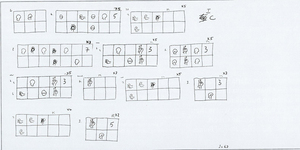

Comments on the score of Hands (1995), the scoring of which was done by Matteo Fargion. Burrows explains the process.

00:44:5900:48:09

Burrows describes the unrealized plan to make an installation with four televisions on the basis of Hands. “We worked for a month or so, we made the installation, and we thought it wasn’t just quite right.” The score that was published in the graphic magazine was in fact prepared for this unrealised installation.

00:48:0900:52:49

Practical arrangements to get the scores, what to publish.

00:52:4900:53:13

Discussion of a detail in Both Sitting Duet: the prescribed moments of watching one another, or the ‘meeting points’ to install a humanity.

00:53:1300:14:00

The scores of Both Sitting Duet ended up being used in the performance as they were made during rehearsals. Burrows explains how movement memory and the (reading of the) score interrelate in peformance. The interview abruptly stops - end of the minidisc.

Tags

00:14:00 00:14:02

00:00:37 00:05:06

00:00:37 00:01:53

00:02:14 00:03:17

00:02:23 00:03:17

00:03:50 00:04:13

00:04:13 00:05:06

00:05:48 00:06:42

00:06:42 00:09:40

00:09:40 00:16:44

00:12:35 00:15:26

00:12:35 00:14:02

00:14:02 00:16:45

00:14:02 00:15:26

00:16:51 00:19:45

00:18:57 00:20:48

00:18:57 00:21:22

00:21:22 00:22:54

00:21:22 00:27:32

00:21:22 00:22:55

00:23:28 00:25:08

00:25:55 00:26:28

00:26:34 00:28:06

00:28:06 00:28:51

00:28:51 00:29:49

00:29:49 00:35:29

00:34:09 00:35:29

00:35:12,684 00:36:46

00:36:49 00:38:11

00:39:24 00:40:06

00:40:14 00:41:02

00:41:08 00:41:27

00:41:38 00:48:09

00:47:16 00:47:35

00:49:45 00:50:59

00:50:59 00:51:36

00:54:13 00:55:52

Visuals

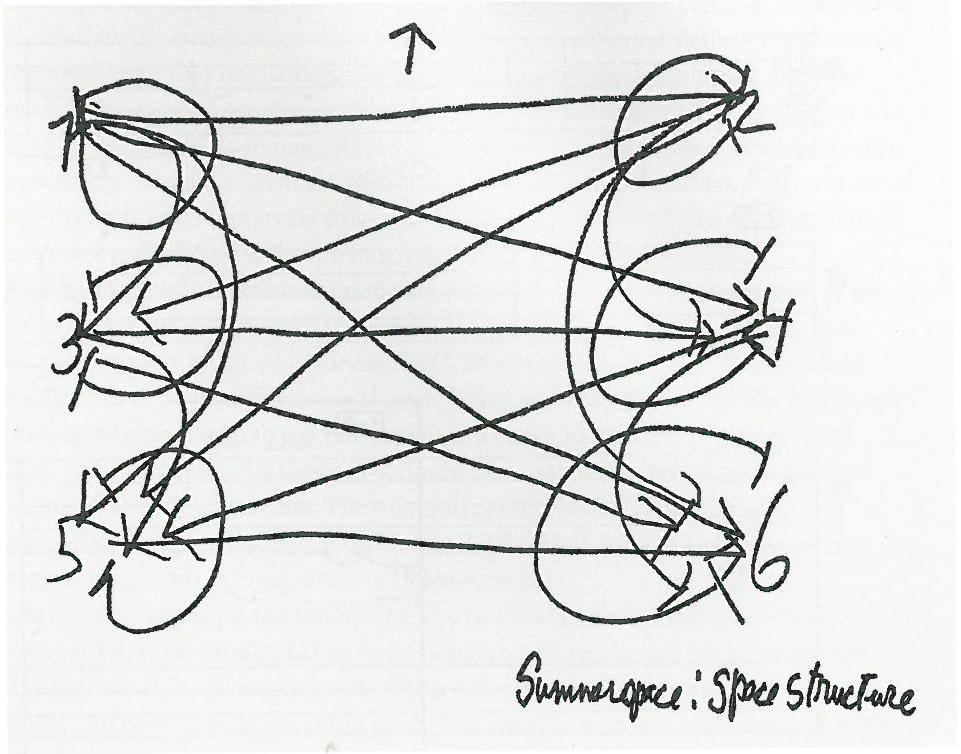

00:02:27 00:38:52

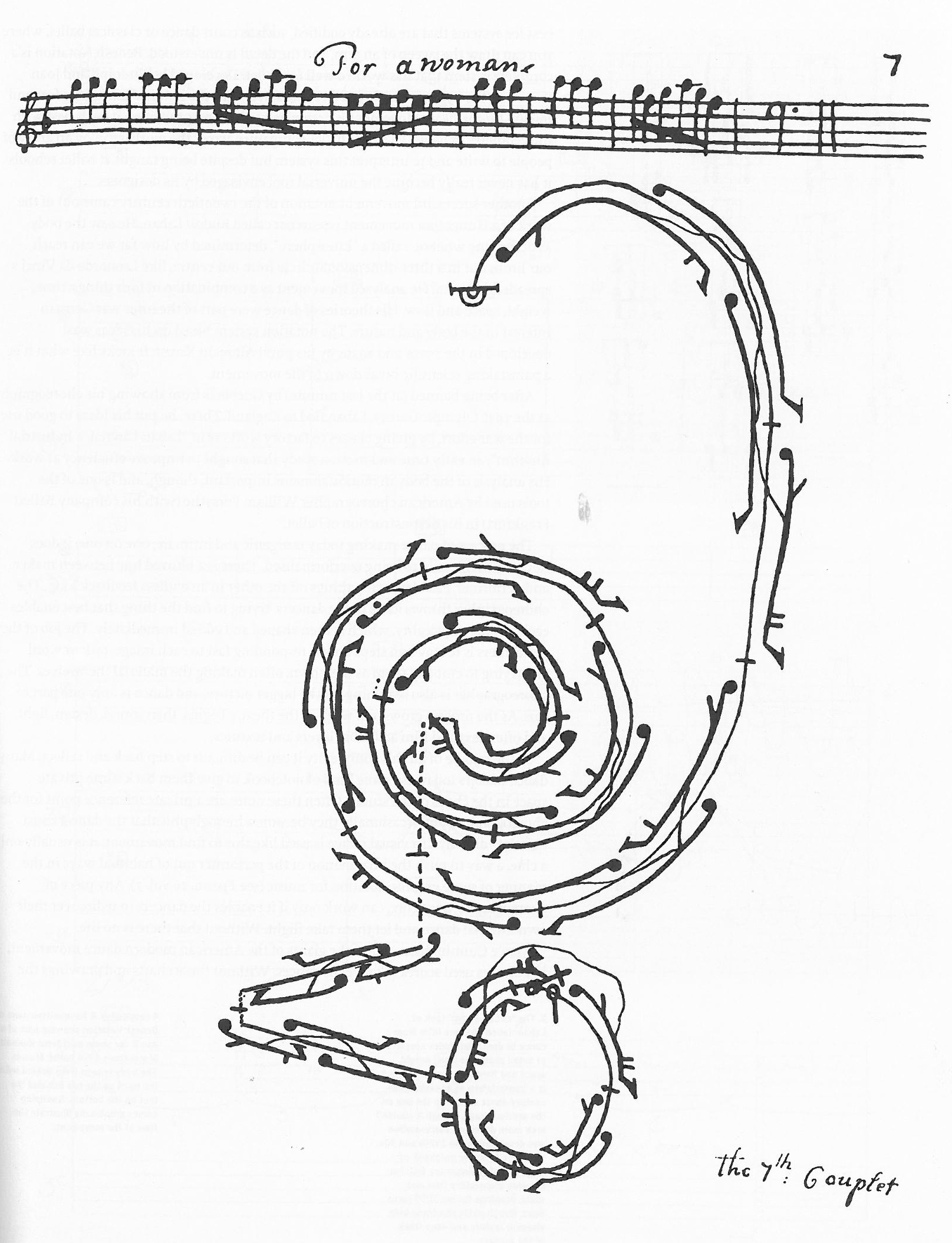

One of the pages from the score of The Stop Quartet

This score shows part of the opening duet of the piece. Further pages and more detailed information about The Stop Quartet can be found on Jonathan Burrows’ website.

00:25:16 00:28:06

Video fragment The Stop Quartet

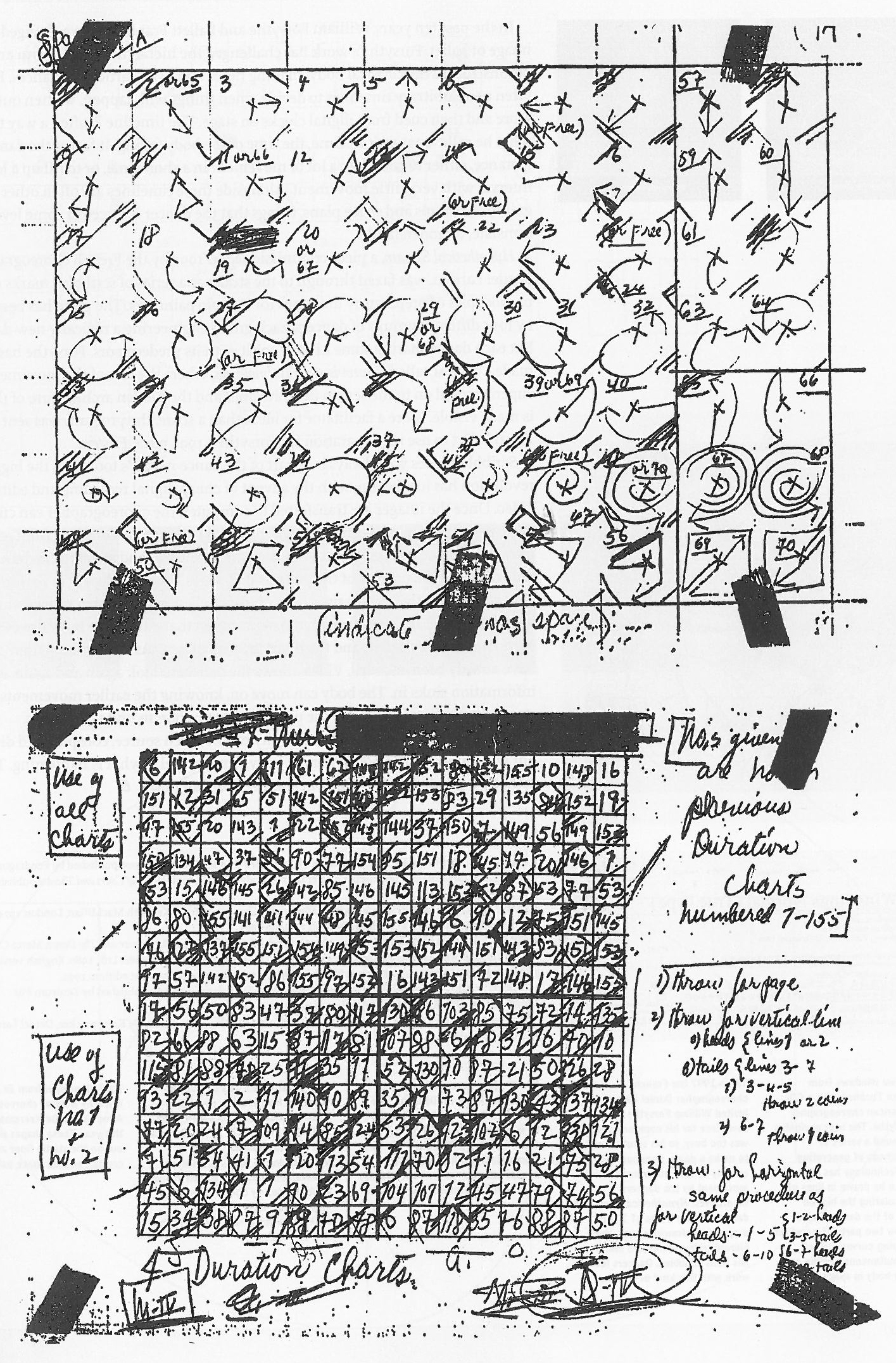

00:44:50 00:47:39

Version two of the score of Hands, a film made by Jonathan Burrows, Matteo Fargeon and Adam Roberts in 1994.

The image was first published in the essay Time, Motion, Symbol, Line (Eye Magazine, 2000)

00:49:54 00:51:30

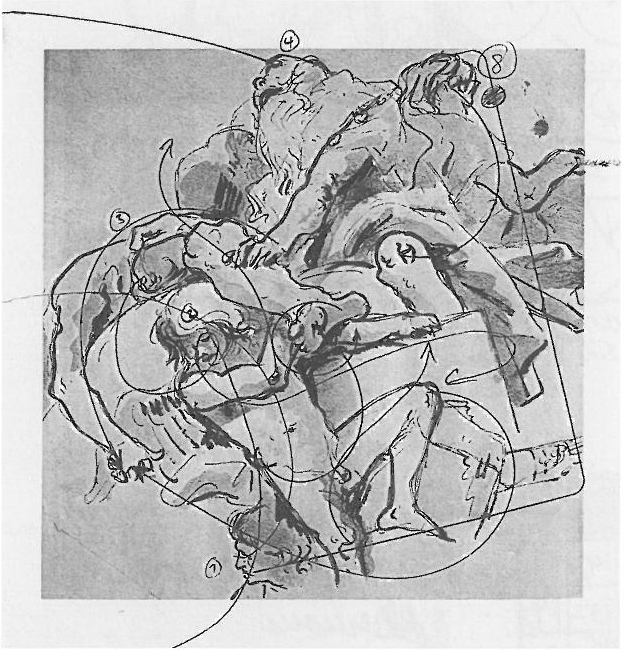

Two scores of Both Sitting Duet, one by Matteo Fargion and one by Jonathan Burrows

00:52:41 00:54:00

Video fragment Both Sitting Duet

EXTRA: Essay by Jonathan Burrows, ‘Time, Motion, Symbol, Line’ (2000)

About the essay

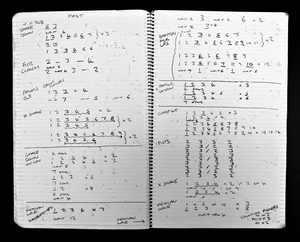

Time, Motion, Symbol, Line’ is an article on scores written by Jonathan Burrows for Eye Magazine, The International Review of Graphic Design, Issue 37 Volume 10, Autumn 2000. The brief for the text was to provide a non-dance readership with some context to understand and follow the graphic nature and pleasures of different kinds of scored dance.

Many thanks to Jonathan Burrows and Eye Magazine for their permission to republish this text.

The article includes a text essay by Jonathan Burrows and 20 annotated illustrations of scores by choreographers Kellom Tomlinson, Laban, Rosemary Butcher, Kenneth Macmillan, Merce Cunningham, William Forsythe, Jonathan Burrows and Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker.

Essay

Choreographers through the centuries have made brave, often beautiful attempts to visualise and record their work, yet scoring a moving, dancing body in four dimensions remains elusive.

Western classical music developed the way it did in part because it found a way to translate what was happening on to paper and literally “see” it in the mind’s ear. Dance has never really found such a system, or at least not one as succesful or durable. How do you “see” four dimensions at once? How do you catch the shifting and subtle changes of dynamic in the body? Writing dance is the exception rather than the rule, and the impossibility of pinning it down has become a quality of the artform, a defining freedom. Dance can go on re-inventing itself, always concerned with the authenticity of the moment, always free of its own history. Yet dance-makers have at times needed some way of recording their work, an overview, a way of reading and writing movement in time and space. The results are a private but often beautiful code.

Each act of choreography is an attempt to create a new language with the body, and each coreographer has a unique voice and an individual way of communicating that voice. Dance-makers will use whatever is at hand that enables the translation of sensation, ideas or feeling into movement, and that helps communicate and record the work. Notation divides into two kinds: the various attemtps at a complete system to write down work that already exists; or the score as a notebook, a tool to find something new. Western theatre dance is a relatively young arform with its origins in the spectacles of the seventeenth century French court. So we begin with the body as site of wealth and status, an image still persisting in the classical ballet that grew out of it. However, the twentieth century saw dance place itself at the centre of rapid change that was Modernism, and out of this came an explosion of new forms. Whereas ballet took 300 years to develop, this new dance enoucraged the individual and evolved rapidly. Dance-makers such as Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham began to invent their own techniques, usually modelled on how they moved and with far more complexity of twist and fall.

In the 1960s the dancer-choreographer hierarchy itself started to be questioned, and improvisation asserted itself as an important tool again. Today a dancer can draw from many different movement philosophies, and be expected to share the making of the work with the choreographer. All of this poses a problem to the complete notation systems, which are slow to use, but it has let to some wonderful uses of graphic scores and notes by contemporary dance-makers.

The first commonly used methods of scoring dance are the elaborate curling “track drawings” of the eighteenth century. These doucments shorthand the basics of each dance, dealing mainly with the feet and where to go in the space, and assuming that the style of the period is understood by the dancer. Like other dance graphics, they carry something of the quality and spirit of the thing itself, a kind of aristocratic grace.

It is difficult to write the detail of the body in dance once you get into the torso rapidly spiralling, with arms and legs moving out of sync. Complete notations work best for systems that are already codified, such as court dance or classical ballet, where you can draw the sweep of an arm, and the detail is understood. Benesh Notation is a complete system that has worked well for ballet. Developed by Rudolph and Joan Benesh in the 1950s, it employs a five-line stave, with the bottom line for the feet and the top for the head. Movement is drawn as curves across the lines: it deals best with the geometry of ballet. Classical ballet companies across the world employ an army of people to write and re-interpret this system but despit being taugth at ballet schools it has never really become the universal tool envisaged by its designers.

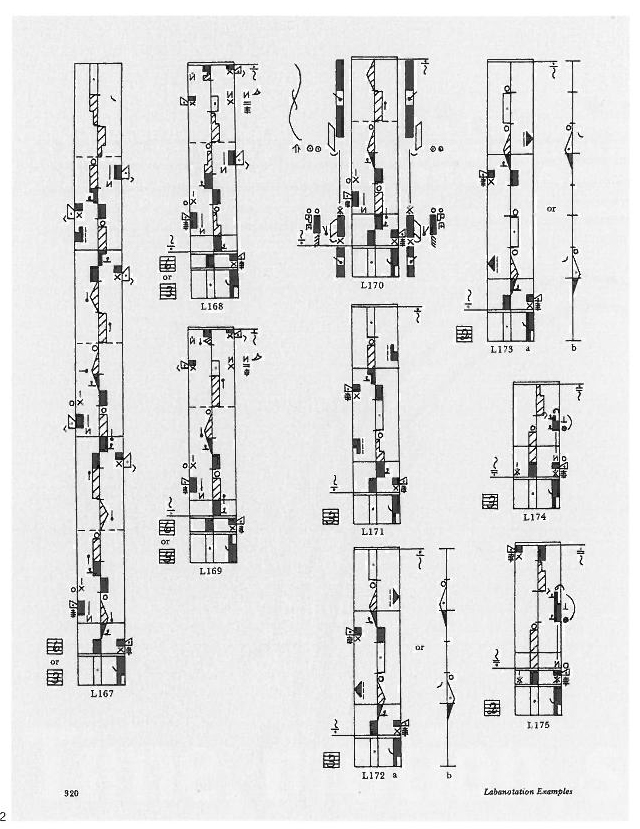

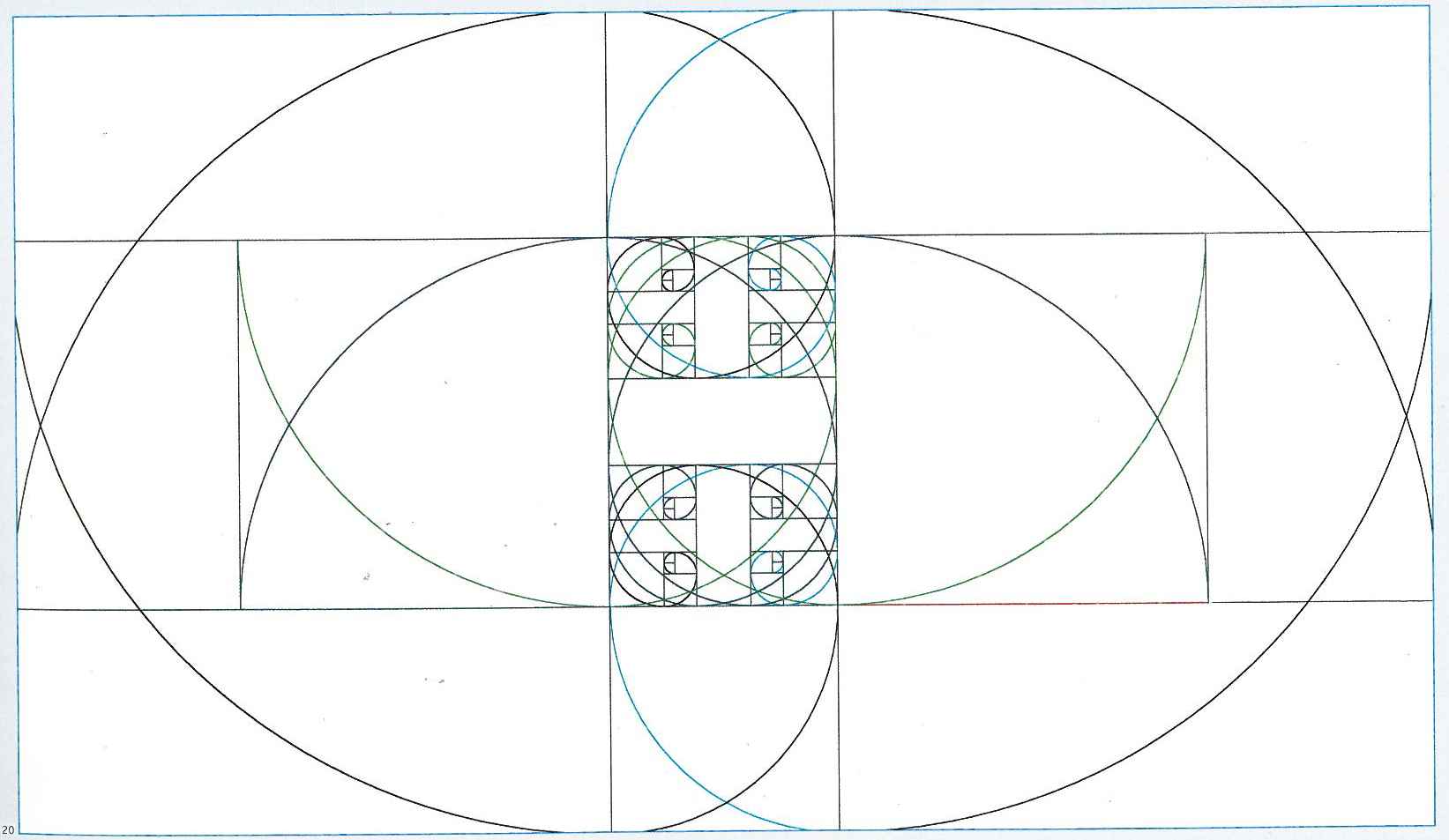

Another succesful movement notation of the twentieth century came out of the work of a Hungarian movement researcher called Rudolf Laban. He saw the body as occupying what he called a “kinosphere”, determined by how far we can reach our limbs out in a three-dimensional circle from our centre, like Leonardo da Vinci’s spreadeagled man. He analysed movement as a combination of four things: time, weight, space and flow. His theories of dance were part of the inter-war German interest in the body and nature. The notation system based on his ideas was developed in the 1920s and 1930s by his pupil Albrecht Knust. It looks what is is: a painstaking scientific breakdown of movement.

After being banned (at the last minute) by Goebbels from showing his choreography at the 1936 Olympbic Games, Laban fled to England. There, he put his ideas to good use for the war effort, by giving classes to factory workers in “Laban-Lawrence Industrial Rhythm”, an early time-and-motion study that sought to improve efficiency at work. His analysis of the body in motion remains important, though, and is one of the tools used by American choreographer William Forsythe (with his company Ballett Frankfurt) in his deconstruction of ballet.

The process of dance-making today is organic and intimate, one on one: it does not lend itself easily to being overformalised. There is a blurred line between maker and performer, each bouncing things off the other in an endless feedback loop. The choreographer throws ideas to the dancers, trying to find the thing that best enables each unique physicality, which is then shaped and edited immediately. The job of the perfomers is to stay two steps ahead, responding fast to each image, task or word and trying to embody them as their own, often making the material themselves. The choreographer is also searching for the bigger picture, and dance is only one part of this. As the process grows and work in the theatre begins, then sound, design, light, and often text and film add more layers and textures.

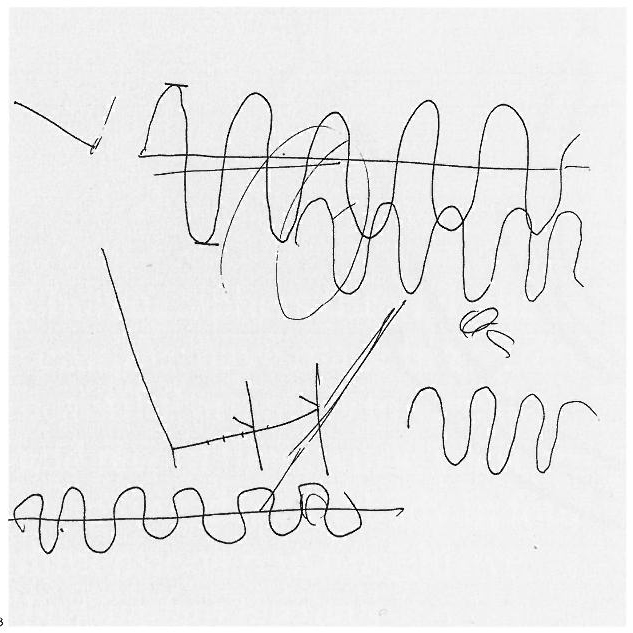

In the middle of this complexity it can be difficult to step back and reflect. Many dance-makers today use some kind of notebook to give them back some private space in the chaos of the studio. Often these notes are private reference point for the choreographer, but occasionally they become a hieroglyphic that the dancer must translate directly. If a visual image is used like this to find movement, it is usually only a clue, a way to push the imagination of the performer out of habitual ways in the manner of some graphic notation for music (see Eye no. 26 vol. 7). Any piece of choreography, any score, can work only if it enables the dancers to rediscover their own internal dance and let them take flight. Without that there is no life.

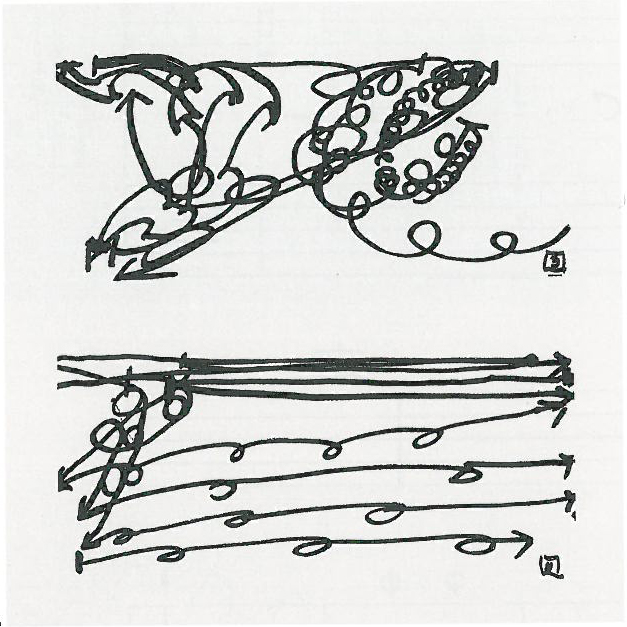

Merce Cunningham, one of the giants of the American modern dance movement, has always used scores to make his dances. Without these charts and drawings the complexity of spatial and rhythmic detail in his pieces would be impossible for him to orchestrate. Cunningham’s scores inform the whole idea and landscape of each piece. It is probably his work with the composer John Cage that influenced this unique and musical approach to dance-making, starting with the rhythmic structures they shared in the 1940s. These structures divided time mathematically into pre-decided “parcels”, which each could fill in his own way. This experience of working in parallel but without being tied to each other was followed by their discovery in the 1950s of chance methods of composition. Cunningham would have a chart for each aspect of the dance, with dice to be thrown for every possible choice of time, space and movement. The process was laborious, but the pieces that emerged from it led to a new way of seeing performance itself. Multiple events could unfold on stage at the same time and the overlap of different elements was constantly shifting and open to change.

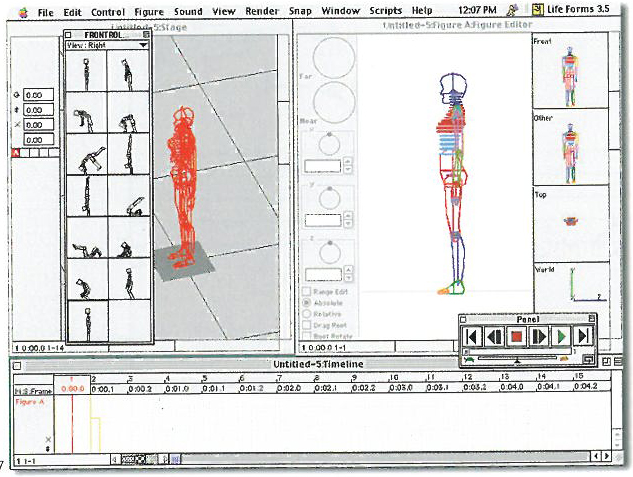

In the past ten years, finding it harder physically to work out the phrases from his charts, Cunningham has turned to computer technology. The Lifeforms software was developed with his help from an animation program. It gives you a digital body and a library of shapes, a timeline for each body in the piece, and a stage that can be looked at from any angle. The current obsession with all things digital means that these pieces are marketed as “cyberdance”, but they are logical continuation of a way of working Cunningham has followed for years. That this is another tool, another way of enabling the events itself, is what makes it radical. In his short autobiographical text, Four Events That Have Led to Large Discoveries (1994), Cunningham lists rhythmic structure, the discovery and application of chance procedures, film camera techniques and the use of software as the moments of important change in his work.

In the past ten years William Forsythe and Ballet Frankfurt have changed the image of ballet. Forsythe’s work has challenged the hierarchies of the form and deconstructed the classical body, making fierce and hyper-articulate dances. He has often used arbitrary timelines to decide when things will happen, written out as a score and then cued from digital clocks on stage. The timeline is often a way to pervert what he calls “anatimical” time, the time of the body falling. It forces the dancer, for instance, either to complete a lot of movement in a short time, or to fill up a long interval with very little movement. Alongside these timelines are often other graphics, cut-ups and space palns, things that the dancer is forces at some level to translate, to understand.

Hypothetical Stream, a piece commissioned in 1997 by the French choreographer Daniel Larrieu, was faxed through to the studio as a series of scribbled marks over photocopies of preparatory drawings for Tiepolo paintings. The piece has been remade by four different groups of dancers, each group engineering a radically new dance, but each dance sharing some kind of spirit with it predecessors. Forsythe has also made a CD-ROM called Improvisation Technologies, where the line of the movement is superimposed on the screen in white lines and the hidden architecture of the dance is made visible. More a facilitator for ideas than a score, the program was sent to the Royal Ballet to use in preparation for Forsythe’s 1994 piece Firstext.

Scribbled notes will always be part of the dance-maker’s tools, but the biggest revolution has just begun, with the advent of cheap digital recording and editing on video. Once the images are transferred to computer, the choreographer can cut and paste instantly, sculpting the shape of the event in time and sampling from any number of process tapes. Improvisations can be relearnt and a record can be kept not only of finished work but of the piece as it changes, grows or decays in performance. This is a tool for the dancer also, since one of the best ways to learn movement is to see it. When we see a movement, the neurones in that part of the body fire even if we do not actually move, and the brain immediately scans for similar patterns that have already been encoded. Video allows the dancer to look again and again as the information sinks in. The body can move on, knowing the earlier movements are stored safely on tape, and free the physical imagination to find new things.

The ideas that underpin choreography can be a rich source, complex and diverse, but watching dance is no mystery: what you see or feel is what is happening. The joy is that we are all silently skilled in reading body language.

Pictures that accompany the essay

Dance notation by Kemmom Tomlinson, 18th century

Labannotation

Notes Rosemary Butcher

Benesh notation

Merce Cunningham

William Forsythe

Jonathan Burrows

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker

Credits of pictures

(1) Example of notation by Kellom Tomlinson from A Work Book by Kellom Tomlinson published by Pendragon Press, 1990.

(2) Example of Labanotation by Mireille Backer from Wendy Hilton’s book Dance of Court and Theatre published by Dance Books Ltd, 1981.

(4). Extract from “The Beggars Dance” from Manon Act I, Choreography (c) Kenneth MacMillan, London, 1974. Benesh Movement Notation (c) Rudolf Benesh, London 1955.

(5), (6), (8) and (9) Extracts from Merce Cunningham’s notebooks published in The Dancers and The Dance, Merce Cunningham in conversation with Jacqueline Lesschaeve, published by Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd., 1980. English verion, 1985.

(7) Window from Lifeforms software published in Macromind Paracomp Inc., first edition, 1992.

(10) and (11) Windows from William Forsythe: Improvisation Technologies, a CD-ROM published by Zentrum Für Kunst und Medientechnologie Karlsruhe, 1999.

With thanks to Rosemary Butcher, Katie Duck, William Forsythe, Anne Theresa De Keersmaeker, Daniel Larrieu and Russell Maliphant.