Scores

00:03:09 00:08:32

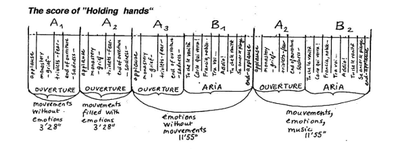

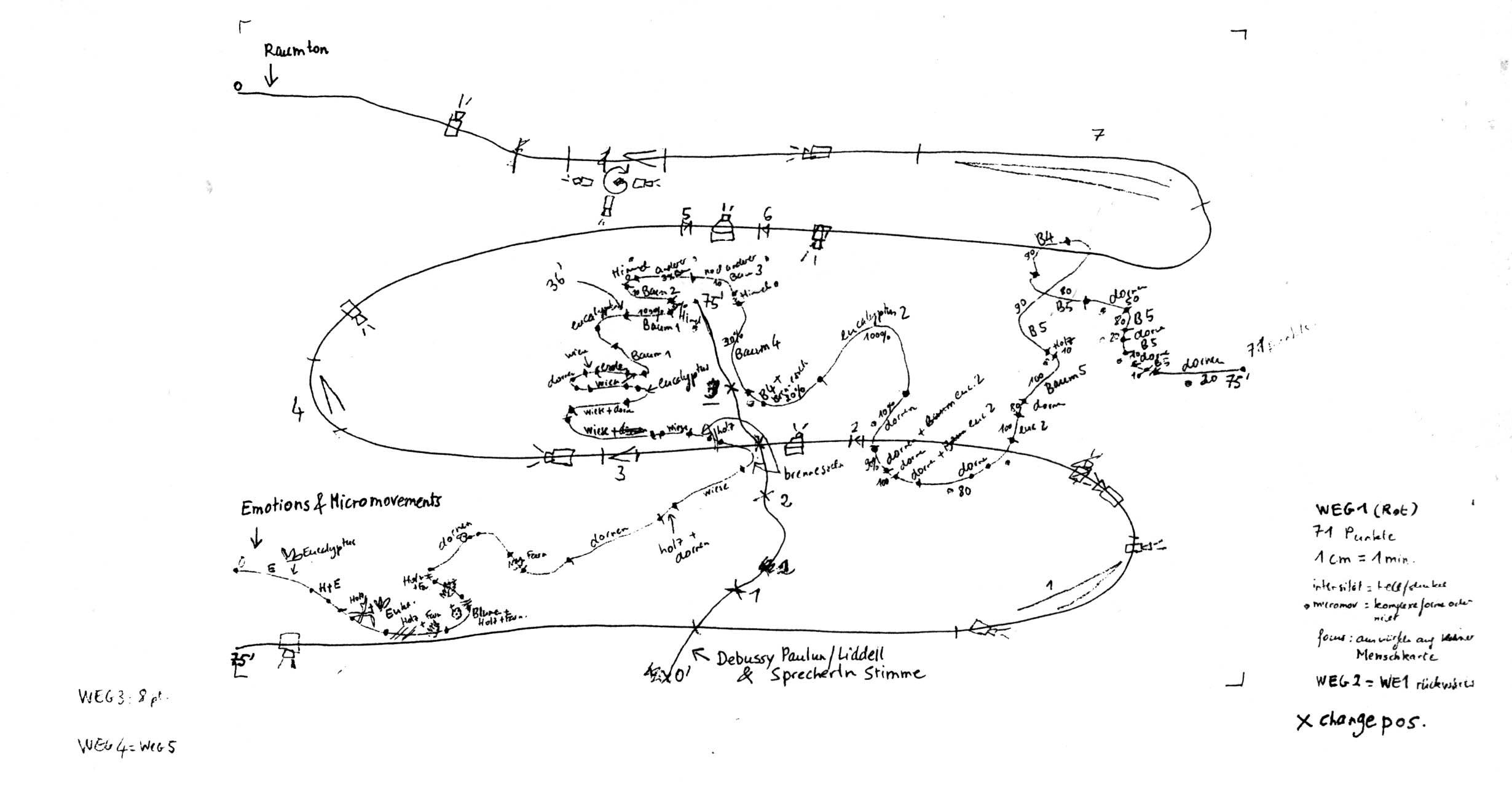

The score of Holding Hands.

00:11:31 00:14:41

00:18:1700:18:44

00:18:4400:20:01

00:20:0100:20:21

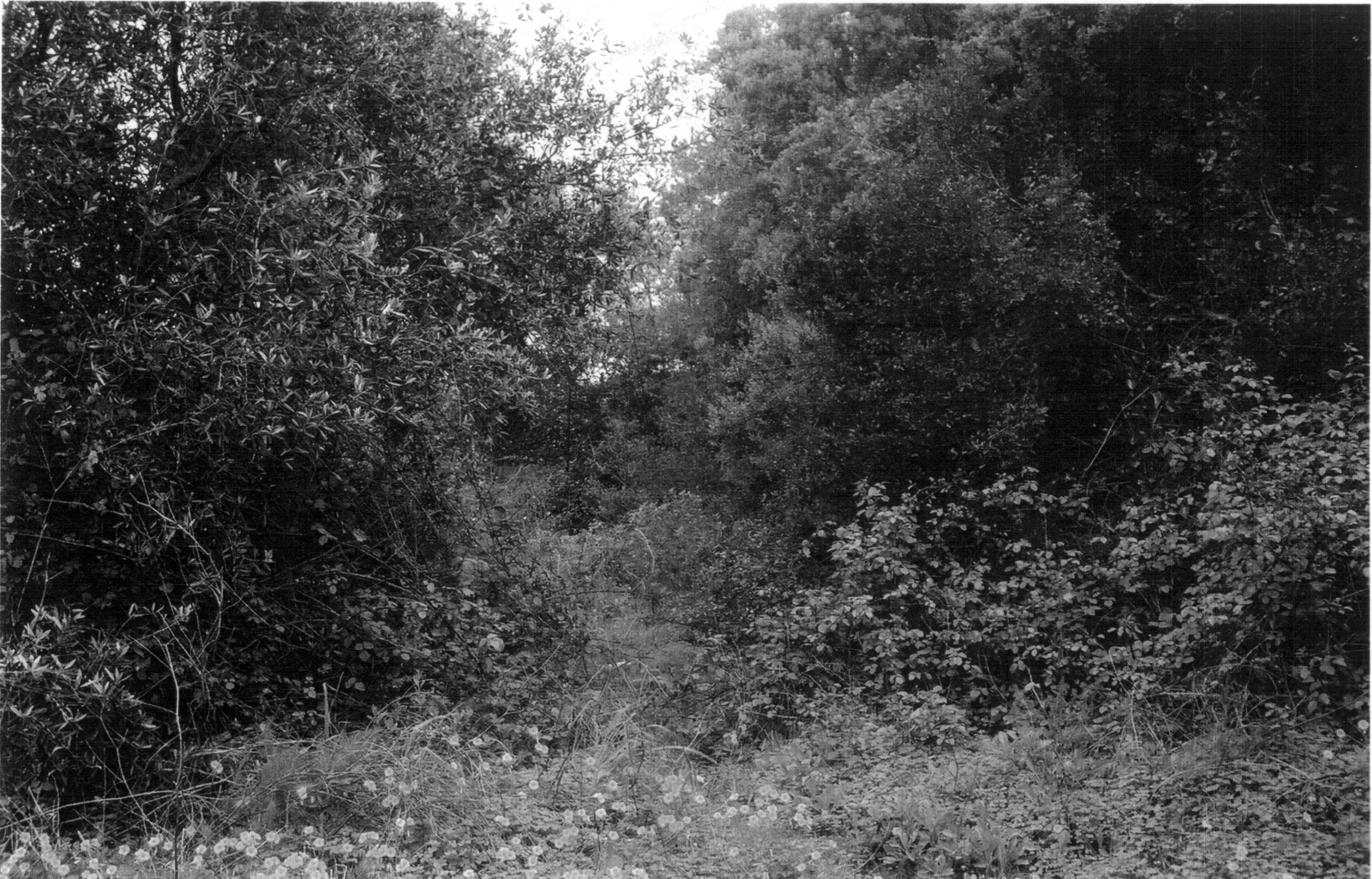

Photograph chosen by Antonia Baehr, evoking Claude Debussy’s L’après-midi d’un faune.

00:20:21 00:25:02

Bonus Tracks

In these bonus tracks Antonia Baehr elaborates on specific notions that were not touched upon in the original interview in 2005.

On Gertrude Stein and landscape

Recorded in Berlin, 2011.

On the term “score”

Recorded in Berlin, 2011.

Visuals

00:00:34 00:02:54

Holding Hands (2001) Photo: Stefan Vens

00:24:22 00:27:21

ZARRILLI, Phillip, (ed.), Acting (re)considered: A theoretical and practical guide, Routledge, New York, 2002.

00:34:5300:41:14

Un après-midi (2004) Berlin Version, Podewil, with: Derek aka E. Cattell, Steffi Weismann, Hr. Bert aka Fr. Honeit, Barbara Loreck

Photo: Stefan Vens

00:41:1400:44:11

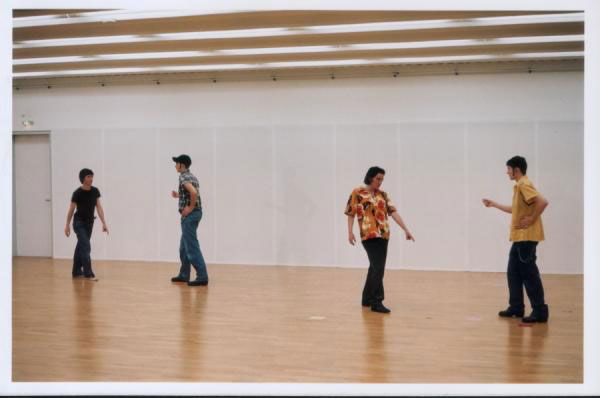

Un après-midi (2004) Vienna Version, Tanzquartier, with: David Gurrola, Josh Macgyver, John Player, Marco Sonnleitner

Photo: Vladimir Miller

00:44:1100:48:07

Un après-midi (2004) Berlin Version, Podewil, with: Derek aka E. Cattell, Steffi Weismann, Hr. Bert aka Fr. Honeit, Barbara Loreck

Photo: Stefan Vens

00:48:07 00:51:00

Eszter Salamon, Reproduction (2004)

Photo: Bruno Pocheron

Audio

00:00:00 00:58:23,420

Video Un Après-Midi

Video registration Un Après-Midi #8, 02/12/2004, Valenciennes.

Synopsis of the interview

The first time that Antonia Baehr used a score in her own work was when making Holding Hands (2001), in collaboration with William Wheeler. Both had a background in collectives, but after this experience they desired to make more clear divisions in regards to authorship. They had an agreement that they would take turns in leading and authoring the pieces they made together. According to that principle, Wheeler had previously made a score-based work Without you, I am nothing together with Baehr (2001). Holding Hands was consequently the piece where Antonia Baehr took charge. Switching between functions was an artistic but also economic decision in lack of production means.

Holding Hands is part of a trilogy — together with Après-Midi (2003) and The Misses and Me (1998) — that researches emotion in the theater, and in particular, invisible humour. By taking out the usual narrative frames, the emotion was rendered isolated, pure and bare. For example, in The Misses and Me only the “laughter” remained.

Baehr describes in detail the way she devised the score for Holding Hands, based on an aria, sung by Callas in Convent Garden. In one of the four sections that structure the composition, Baehr and Wheeler reproduced from a video the movement of the head of Callas. For another section they only performed the emotions as could be deducted from the score of Verdi, masterclasses Callas gave and commentaries of musicologists. In the end the piece was entirely performed, with all emotions, movements of the head and postures, in playback mode to the music.

Baehr describes that her intentions were not about representation or mimickry of Callas. An analytical approach seemed to her more efficient when studying the effect of emotion in an audience. That’s also why a subtle, naturalistic portrayal of emotions worked better for certain sections (which sections?). This is a recurring theme in the work of Baehr: how is something perceived at the other end by the spectator? Later the score got used by other performers, like Sophia New and Petra Sabish. It was of interest to Baehr to see how the piece would work separate from the performance by her and Wheeler with just the score as go-in-between. In fact, she says, this doesn’t differ much with the way scores function in classical music where the transmission of the author’s work demands an exactitude in performance with little margin for interpretation.

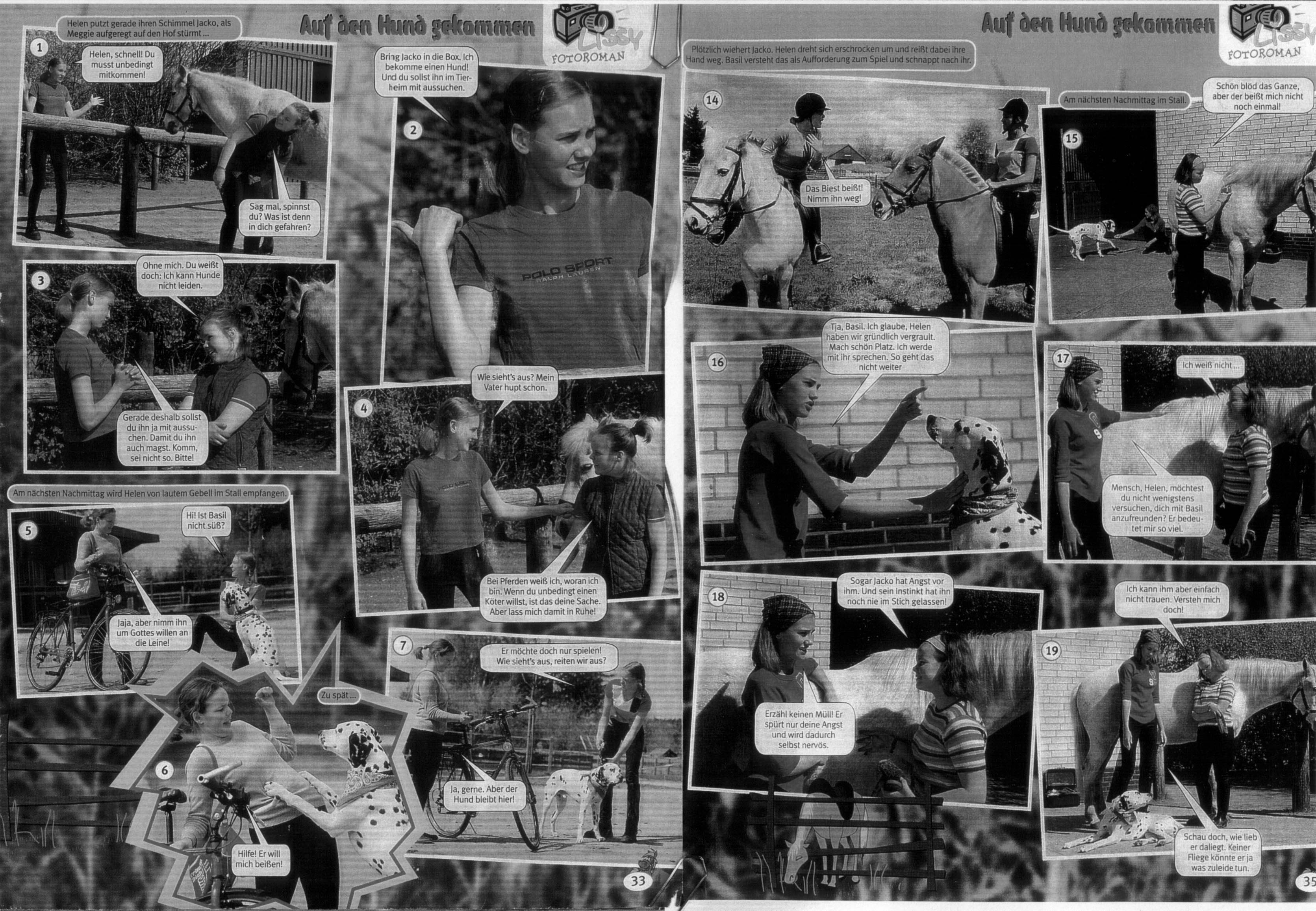

In general, Baehr sees three reasons to use scores. It helped her to find other modes of composition other than the collage techniques of dance theater. It also enhances an aspect of writing and helped her to configure collaboration differently. As for the latter, Baehr goes on to explain this by describing the points of departure for Après-Midi. After having worked on a monologue (an aria) with Baehr as the director of the piece, Wheeler suggested to work on dialogue — both by using dialogue structures as a point of departure for the piece and by looking for another working relation that the directorial one. The dialogue came from Bravo, a popular “cheap” photo roman, with strong heterosexual normativity. So Baehr explains at some point in the interview that this was in contrast to the high art opera of Holding Hands. They decided to work with interpreters, and developed a complex and layered system of score making, that ultimately involved Antonia Baehr, Wiliam Wheeler and Henry Wilt. Later, at the end of the interview, Baehr will relate this to issues of SM. It is an ongoing theme, too, in her work: to question relations of production and relations in general, attempting to question conventional power structures, either by displacing them or by emphasizing them even more.

Baehr has sometimes a hard time to remember all the steps in the score, and the interview is partly a reconstruction of the inner mechanisms, step by step. It’s a detailed scrutiny; on the way many themes are touched: working with a Cage-score, the theme of landscape in Un après-midi, the application of Alba-emoting techniques, an acting model that contrary to method acting (using memory) looks for a purely physical approach, etc.

Of Un après-midi two versions exist that differ in length and the distribution of speed (tempo). The second version came after angry audience reactions to the first version, which thwarted many expectations in regards of development, dramaturgy, etc The interview ends near the end with addressing the choice to work with dragkings. Baehr mentions an incident in Leipzig with two dragkings and a man, which helped to finetune the gender policy. A comparison is made with Reproduction by Eszter Salomon, for whom Baehr was gender consultant. The interview ends with returning to the theme of collaboration, this time rephrased by using SM as an analogy.

Chronology

00:00:0600:01:32

Baehr explains that working with scores started in fact already before Un après-midi with Holding Hands. She sketches the context of working collaborations with William Wheeler, the system of alternating roles of leading and the need to devise collaboration differently through working with scores.

00:01:3200:02:30

Holding Hands was part of a trilogy together with Un après-midi and The Misses and Me. Baehr surveys the general theme of the trilogy: a research on emotion and the effect on the audience.

00:02:3000:04:03

Description of the score of Holding Hands, based on an aria of Maria Callas in concert at Convent Garden. The entire aria is used, from ouverture to the applause by the audience. The score shows in four sections four reworkings of this aria, isolating every time different parameters.

00:04:0300:05:00

Baehr did not aspire mere representation or mimickry, but an analytical dissection of head movement, posture, emotion, etc, before mixing them in the full-on playback.

00:05:0000:06:08

«The thing was to do it to see what it produces in an audience. We also realized that it needed a very naturalistic representation of emotions. It had to be very small, actually.»

00:06:0800:07:14

Holding Hands still tours. It’s one of the pieces that tours most. It was also performed in a version by other performers, like Sophia New and Petra Sabish.

00:07:1400:08:09

Baehr mentions some upcoming showing dates and asks Ludovic not to tell the ending to his friends who may come to see the show. The piece works better when one does not know the ending.

00:08:0900:09:21

Baehr sums up three major reasons why she uses scores: avoiding classical dramaturgy based on narrativity that is not indebted to collage aesthetics in dance theater; a practice of writing; and collaboration.

00:09:2100:11:31

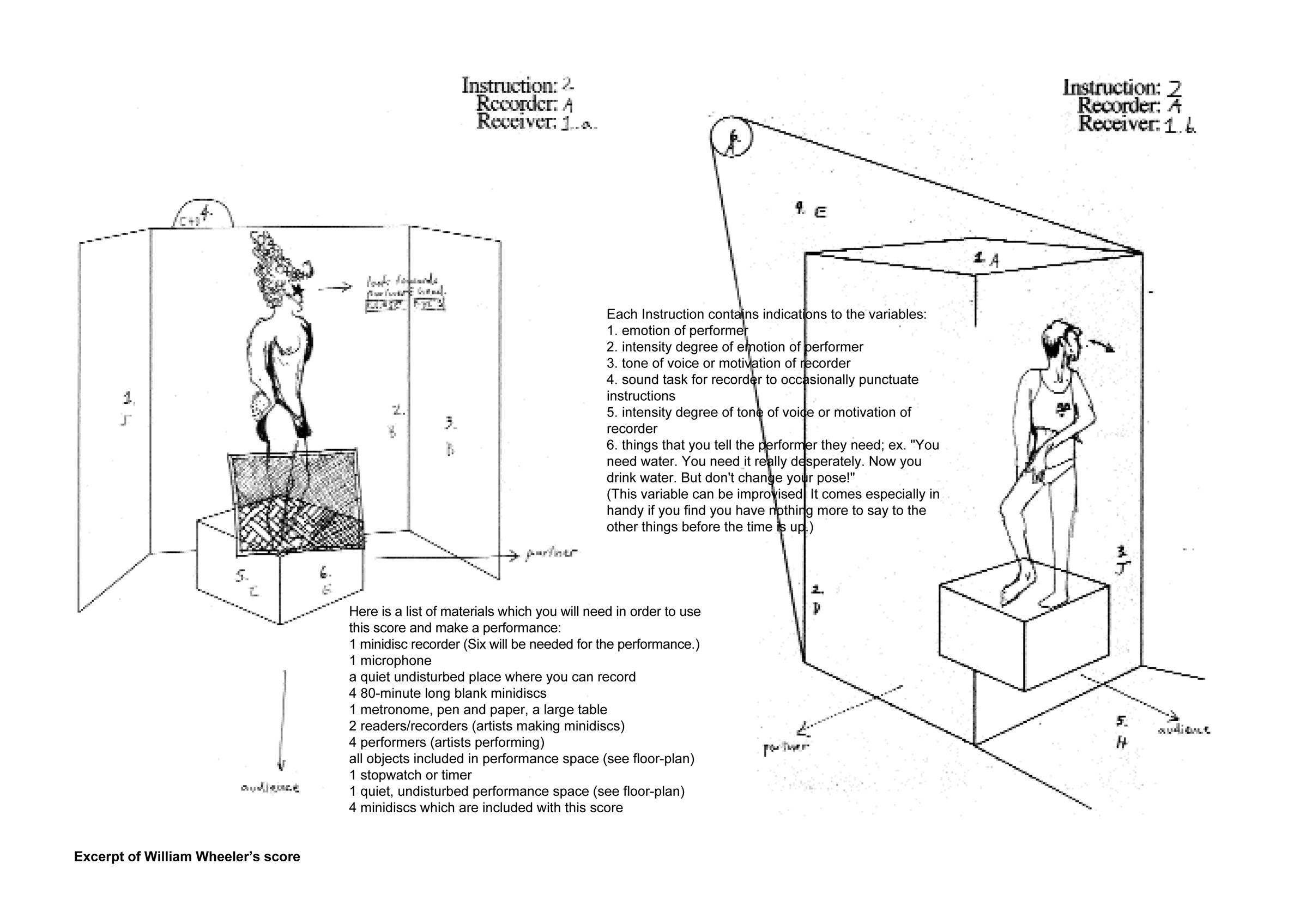

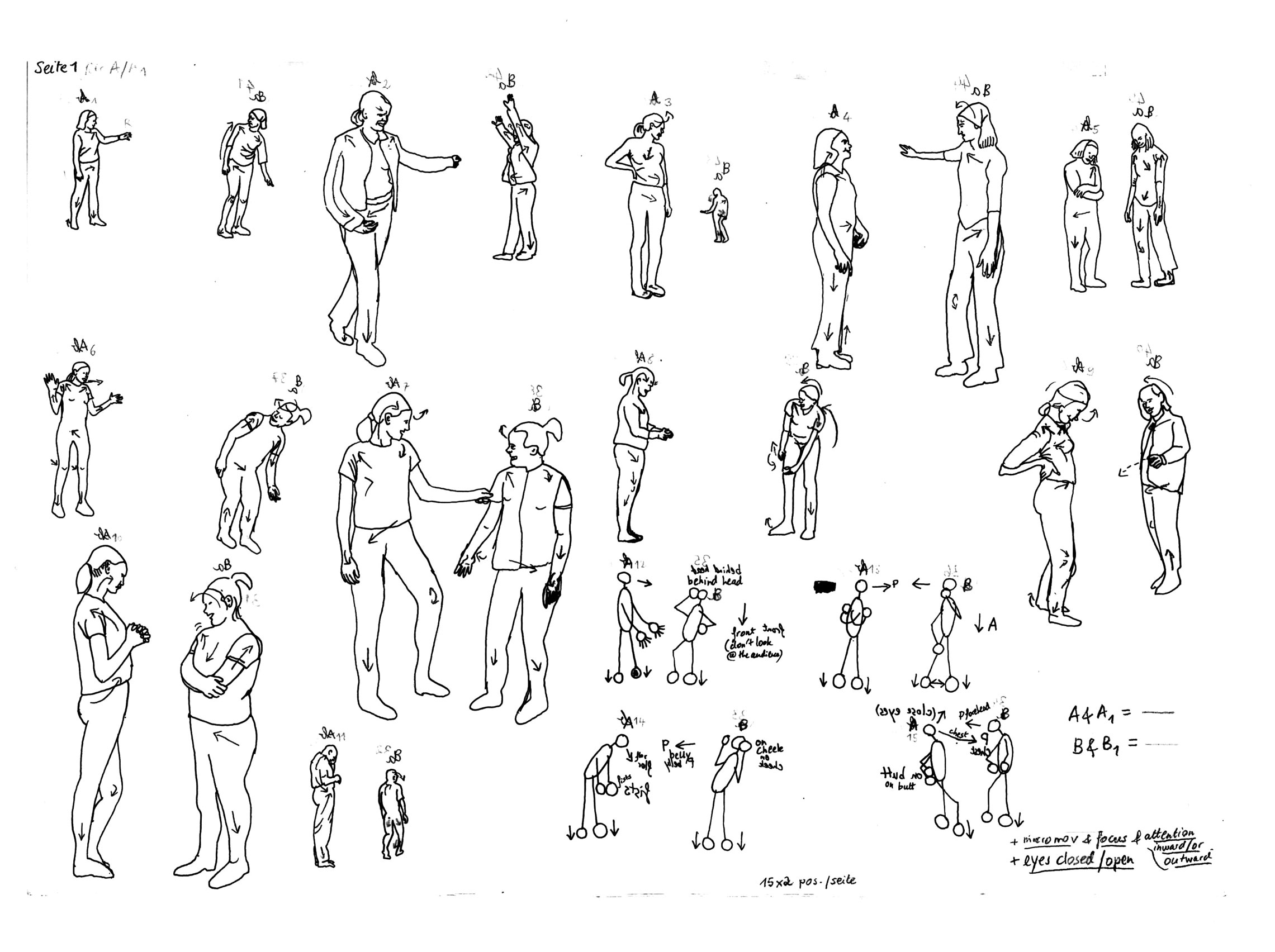

Baehr and Wheeler agreed on five ingredients to be used for the scores, also to be used other score-makers. In the final stage the score ends up in a set of instructions on mini-disk-players for four performers.

00:11:3100:14:41

Baehr speaks some of the two scores. The score of Wheeler came in the form of a book, but was never developed all the way into performance, because of lack of time.

00:14:4100:16:13

The ingredients proposed for the score of Baehr (it’s a score for somebody to make a score) are amongst others: Jamie Lidell’s version of L’après-midi d’un faune “Taught to box”, on the CD Replay Debussy after the concept of Christian von Borries.

00:16:1300:18:46

The second ingredient is a score from Songbook (Solo for Voice 3) by John Cage, which is a map-score for voice. Baehr explains the principles of this score. The third ingredient is to use a photo roman (LISSY Nr. 8/01, Fotogeschichte Auf den Hund gekommen, BRAVO Nr. 8/02 Foto-Love Story Extra). The score of Baehr instructed someone to take a photograph and draw a path on it, or several pathlines/timelines. One is for emotion, one for positions, and a third for the speaker (who reads for the minidisk: William or Antonia).

00:18:4600:19:12

In the first version Baehr did not change anything. It did not matter if something was thrilling or not.

00:19:1200:24:22

Baehr shows the photo that she selected to draw the map on. Se reads from her instructions. She mentions paths that are for emotions and micro-movement. There are instructions for intensity and dynamic. All was done very accurately. Baehr reads also from an analysis of the vegetation (Eucalyptus) In addition, emotion cards were used.

00:24:2200:27:21

Van Imschoot reads one of the emotion cards, portraying “tenderness”. It’s one of the examples of how alba-emoting constructs emotion. One can learn about this acting technique through an article in the acting book Acting (Re)considered. A Theoretical and Practical Guide (Worlds of Performance). Alba-emoting is a countermethod to method acting or Stanislavski-based approaches, working with emotional memory. Baehr started to use this method when working on Holding Hands.

00:27:2100:30:00

Baehr continues with a detailed description of the score, and how decisions concerning degrees and intensities were arrived at.

00:30:0000:32:10

Baehr shortened the piece in a later version. She also put a faster part later in the piece, because the audience tended to react aggressively.

“In normal dramaturgies, things don’t go slow again for a longer time after a fast part. If people don’t get the conventions they build up anger. I couldn’t deal with the anger thing, too much explaining.”

00:32:1000:34:53

Usually Baehr starts the performance with a short introduction that mentions that there’s a score and that the performers have never rehearsed it. Everything what is seen by the audience is all happening for the very first time.

00:34:5300:38:10

The instructions given on the minidisc are complex and very difficult to perform precisely. The more detailed you think about the instructions, the more possibilities and/or difficulties arise. Baehr explains that the idea of collaboration is often accompanied by the notion of freedom.

00:38:1000:41:14

Baehr further explains with the score how this was further translated into instructions for the minidisc.

00:41:1400:44:11

Comment on the performance by Finn Random.

00:44:1100:44:47

Baehr uses on the minidisc scientific terms terms for the description of anatomical body parts. Baehr shows an anatomical drawing that they used. It’s using a woman as a model. Van Imschoot points out that this may be funny, since the piece was to be performed by drag kings, whereas the drawings are working with female anatomy. This leads to a discussion of the choice to work with “drag kings” as interpreters.

00:44:4700:48:07

For Baehr the choice for drag kings and queerness was imbedded in the piece. For one thing, it relates to the collaboration between Antonia and William. In contrast to the opera and high art material that was used in Holding Hands, the choice to work with pulp material (the photo novel) and counter its heterosexual normativity.

00:48:0700:50:19

Eszter Salomon had seen Un après-midi. The way of dressing had interested her a lot in regard to her own project Reproduction. She was going to make a piece for eight men and eight women. Budget-wise it was interesting that all parts could be done by the women. Baehr became a gender consultant. She later realized it was more a matter of costumes than really working on gender. Part one comes the closest to Un après-midi, but the second part is different: in that part one can see that the men were actually women and the normal ‘male’ gaze of spectator is activated again.

00:50:1900:51:00

A big difference between Reproduction and Un après-midi is that the latter works with desire; the desire to become a man and to be told what to do for the length of the performance.

00:51:0000:53:23

In Leipzig there was a conflict with two real dragkings (casted through a website for dragkings, Dragkingdom) who objected to a man being in the cast. Being a dragking is about reappropriation of male power so it’s necessary to have lived as a woman.

00:53:23 00:58:23,420

The nice part of Un après-midi is that it becomes political in the act of doing the piece, through dialogues with the interpreters, Baehr explains. Also the discussions on what it means to be bossed around, are very interesting to her. She relates this to sm. The interview further looks for analogies between SM-practice and collaboration models. Van Imschoot distinguishes the sexual contract between SM practitioners (as model to discuss functions and roles in collaboration) with the capitalist model of employee and employer.